Quanesha Moyer arrived at her first foster home when she was five years old. She was nonverbal. Or so they thought. Quanesha knew she could speak, but the unfamiliar adults in her life did not. This suited her until her strong will demanded a voice. At that point, she broke and vehemently declared, “I am a Moyer, and you can’t tell me what to do!” That day, a wave of fury was unleashed, and it raged for more than a decade.

Quanesha was expelled as a first grader. She lived in a long string of foster homes and only attended regular schools off and on. When she exhausted options in Virginia, she was sent to Colorado, Tennessee, and then back to Virginia. Even when attending schools designed for students with complex behavioral and educational challenges, including Rivermont and Minnick, her extreme behavior resulted in confinement at Coyner Springs, a Roanoke Valley Juvenile Detention Center—twice.

At age 16, she was deemed incapable of contributing to society and was recommended to the Department of Corrections, where she would be detained until she turned 21. But teachers from both Rivermont and Roanoke Minnick rallied for Quanesha and stood in the gap. They advocated for her to be held at Coyner Springs until she was 18, at which time her juvenile record would be cleared. “Then, let the world decide her fate,” they argued.

Despite her shocking behavior and her tumultuous background, they believed there was more. They bought time in hopes that Quanesha would come to believe the same.

On her 18th birthday, Quanesha’s juvenile record was expunged, and she was released from detention. She signed herself out of the foster support program, moved in with her oldest brother, and had a life-changing conversation with herself. She remembers thinking: “Self, you do not want to go to prison. You are not meant for jail.” And, in that very moment, she flipped the script.

Quanesha searched for opportunities to be different than what she had been, including attending church, reframing her mindset, and at school. She began work in early childhood development and remained in that field for the next 20 years.

“I was outrageous and out of control for a long time,” Quanesha recalled. “But there were people who saw my behavior and saw something deeper. I couldn’t have done it without them and without God’s grace and mercy. I began living for something beyond myself.”

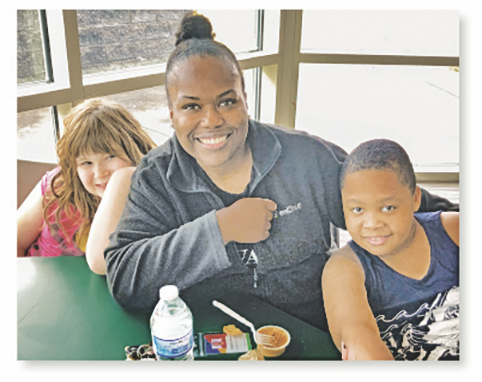

Her resilience is astounding. Her confidence is evolving. Two years ago, she applied to be an assistant teacher at Roanoke Minnick, the same school where she had rebelled many years ago. “I didn’t feel like I was qualified,” she admitted. “But a friend kept saying to me, ‘Who better?’” Her friend was right. Quanesha has profound insight into her students.

“There’s always something deeper driving the behavior,” Quanesha said. “You don’t know what they witnessed last night or when they had their last meal. We feed them breakfast at school, but they may know that they will not have another meal that day. Their behavior is telling us something if we listen.” Quanesha would know. “She is so compassionate with the kids,” said Casi Staton, a long-term substitute who works alongside Quanesha. “She is full of encouragement and sees well beyond their file.”

“I want to be that one voice, that one presence, for that one kid,” Quanesha said. “It doesn’t have to be monumental. Sometimes it is just a single word that a kid will hold onto to get them to the next day. I tell my students that everything in life can be stacked against them, but they can flip the script and say, ‘Nah, I’m going to be someone else.’

Quanesha uses her rugged path for good. Recently, she contacted one of the teachers who had supported her many years ago to say, “Thank you. You saw me.” It was a poignant reunion as he learned how she now “sees” her own students.

“One day, one of these kids is going to say, ‘I remember Ms. Q., the cool teacher who didn’t let me be that person they said I would be,’” Quanesha said. “And that kid will go on to do something different.”

Quanesha is proud of changing the trajectory of her family name, the one she so dramatically defended at an early age. She now has three children of her own, each one an honor student and an accomplished athlete.

“I understand my students because, at one time, I was one of them. I was that noncompetent kid, that misbehaved kid, that hopeless kid,” Quanesha said. “But we can’t stop there, because now I am successful, empowered, and most of all, empowering. I am exactly who they said I couldn’t be.”