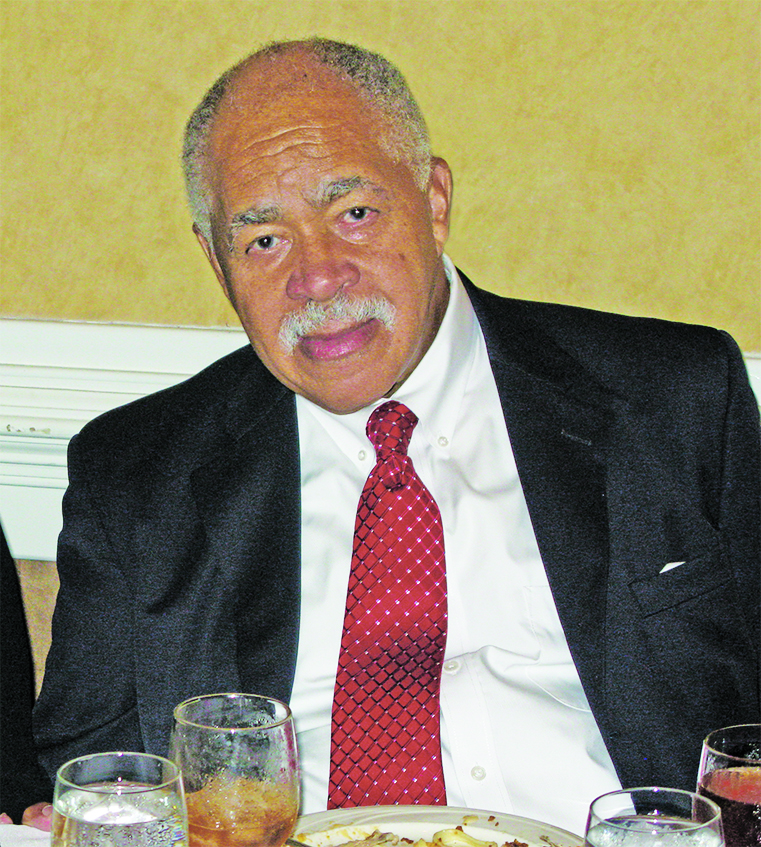

When Roanoke native William Robertson died last year, he left behind a lasting legacy.

Robertson, known as Bill, served as principal of Hurt Park Elementary School before embarking on a life of public service that saw him become the first Black advisor to a Virginia governor and an executive-level decision-maker in five presidential administrations.

Now a group of civic leaders is calling on Roanoke’s school board to name the district’s new downtown administration building after William Robertson.

The school district has received requests from 50 people nominating Robertson’s name to grace the building at 201 Campbell Avenue, which for nearly a century housed The Roanoke Times newspaper. The Rambler received copies of those forms in response to a public records request.

The board this month voted to create a committee that will explore whether to name the building, which the district purchased in October for $5.85 million. Next month, the school board committee will ask the public what to name the building, which is undergoing renovations.

Despite his state and national accomplishments, Robertson’s influence on the Roanoke Valley may be better known by his commitment to establishing a camp in Bedford County that served children and adults with developmental and physical disabilities. Through a fundraising campaign that sold apple jelly across the state, Robertson helped create Camp Virginia Jaycee, which ran from 1971 until its closure in 2017.

Members of the now-defunct Roanoke chapter of the Virginia Junior Chamber, known as Jaycees, have rallied recently to recognize Robertson. The civic organization aims to foster leadership and development skills for young adults.

“Bill is one of those leaders, regardless of race, creed, color, who understood something that was lacking in the Roanoke Valley, and he did something about it,” said Bev Fitzpatrick, a former Jaycees member.

In 1966, Robertson became a member of the Roanoke Jaycees, according to online club history. Fitzpatrick believed that at the time the Jaycees did not allow Black members and that the Roanoke chapter ignored that provision when accepting Robertson into the group.

Presented with a list of possible service projects, Robertson “picked the one no one else wanted: intellectual and developmental disabilities,” the club history says. “Recognizing the value of planned recreation as both therapy and training, Mr. Robertson conceived the idea of asking the Virginia Jaycees to buy and develop a campsite.”

Robertson convinced 140 Jaycee chapters to sell 15-cent jars of apple jelly for one dollar in a door-to-door campaign one Sunday in 1969. The efforts raised $68,000 surpassing a $45,000 goal and established a camp that has served 47,000 residents with special needs.

In 1969, Robertson became the first Black man to run for the Virginia General Assembly. While his campaign was unsuccessful, Linwood Holton — a Roanoke lawyer intent on bringing down the segregationist Democrat regime — appointed Robertson as an advisor when Holton became governor the following year.

Robertson dismantled lily-white state agencies, beginning with a campaign that integrated the incalcitrant state police force.

He went on to serve five presidents, including as head of the Peace Corps for Kenya and the Seychelles beginning under Gerald Ford and as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for African affairs under Ronald Reagan.

The idea to honor Robertson at the building emerged out of the Roanoke Times building itself.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

A 2021 editorial encouraged the city to remember Robertson and noted his alma mater, Bluefield State University, named its library after him in 2019.

When former Jaycee members learned the school district had purchased the former Roanoke Times building, they lobbied on Robertson’s behalf, Fitzpatrick said, including by gathering nomination signatures during luncheons at the now-shuttered Roanoker Restaurant.

“I just think he’s an outstanding candidate for the building to be named after,” said Courtney Hoge, who spearheaded the efforts.

Hoge recalled standing along Campbell Avenue with Robertson selling apple jelly; a club history describes Robertson as wearing a white top hat and coat and tails with “Apple Jelly” embroidered on the lapel during the fundraising campaign.

“He was easy to relate to. Bill didn’t carry anything on his sleeve,” Hoge said. “I just never saw him as someone that was anything other than doing the very best he could for the community as a whole.”

In February, the University of Virginia Press released Robertson’s posthumous memoir, “Lifting Every Voice: My Journey from Segregated Roanoke to the Corridors of Power,” written with Becky Hatcher Crabtree and with a foreword by Holton, who died last October.

“The survivor of a traumatic childhood in the Green Book South, and the witness to his father’s rage over racial inequity, Robertson rose above an oppressive environment to find a place within the system and, against extreme odds, effect change,” the publisher says in a description. “Lifting Every Voice reveals how the advances made during his lifetime were no foregone conclusion; without the passionate efforts of real people, our present could have been very different.”

At a school board meeting earlier this month, board members decided the new administration building is eligible for naming. That kicked off a process that will form a naming committee next month and a public call for suggestions that will be open for the next 60 days.

Committee members will have to weigh other naming suggestions, and the board could decide not to name the building after all, according to the district policy.

The naming committee must include a representative from the school administration, a parent, and a representative from the community, and be made up of between three and nine people.

In voting 4-2 to form a naming committee, the board determined that the petitions on Robertson’s behalf met its criteria that facilities be named “for distinguished persons who have made outstanding historical contributions to the school division, city, state or nation.” The policy also notes that “Strong consideration will be given to the names of women, minorities and other underrepresented persons who have made exceptional contributions to the educational endeavors of Roanoke City Public Schools.”

Board members Diane Casola and Joyce Watkins voted against creating a naming committee.

While board members referred to the district receiving “several” naming forms for the administration building, Robertson’s name was not revealed until the district responded to The Rambler’s public records request last week.

Board member Franny Apel said the board will have to determine whether naming the administration building is an appropriate way to honor somebody and that members will have to consider names submitted by the public as well.

“I would be wary of naming a building because we like the honoree,” Apel said, “because there may be other honorees brought forward that may change our opinion of whether we want it to be named in the first place.”